Demanding that tourists book seven years in advance is eye-catching, if perhaps impractical – a radical solution to a growing issue. You could define the problem as ‘too many tourists’, or ‘the wrong type of tourists’, and the effects are evident.

Last year, 960 million people took a holiday. The UN estimates tourism will produce 5.3 per cent of human-made emissions by 2030. Rising property prices exclude locals from city centres in Auckland to Athens. Then there’s crowds, strained infrastructure, seasonal swings and economies that are over-reliant on visitors’ spending. Venice is a headline example: every year 20 million people stop by this city of 50,000 residents. La Serenissima hasn’t been so serene recently, as it became the first city in the world to charge a tourist entry fee (€5), a move met with protests from Venetians who said it made them feel like they were living in a theme park.

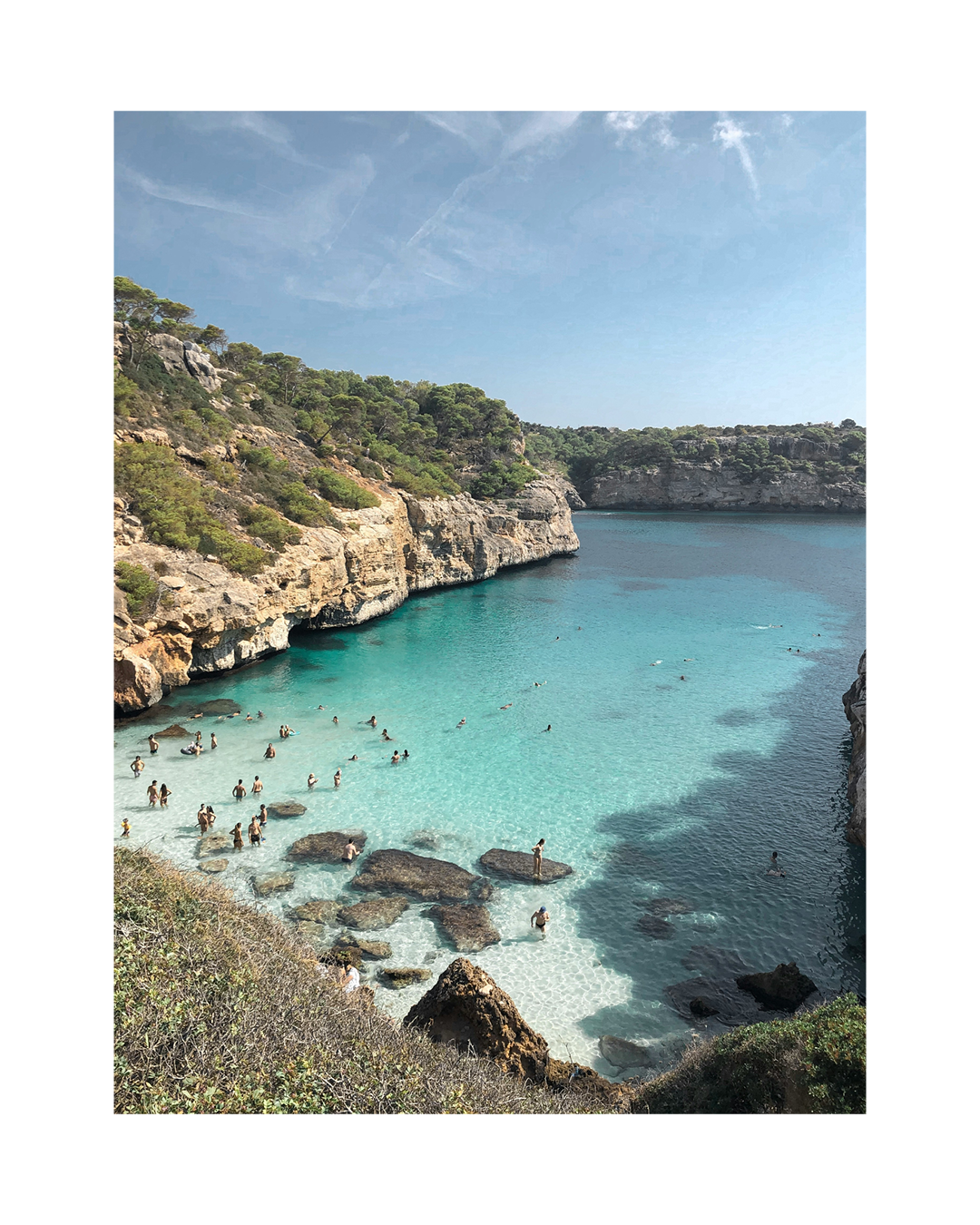

LEFT: SELFIE-TAKING IN VENICE. RIGHT: CALÓ DES MORO, MALLORCA

This summer has seen anti-tourist protests in the Canary and Balearic islands (menys turisme, més vida runs the Mallorcan slogan – ‘less tourism, more life’), following demonstrations in Greece, Austria and France. They’re part of a backlash to a tourist industry that has been growing unchecked since the 1960s. According to the UN, tourism is back to 88 per cent of its pre-pandemic levels. Perhaps those lockdown years of having their cities, beaches and mountains to themselves made locals long for a bit more tranquillity. Increasingly, destinations are imposing measures to reduce, deter or even ban visitors.